tim miller husband

Texans take a addiction of taking matters into their own hands, and Tim Miller is no exception.

One twenty-four hours in 1994, Miller drove to the home of Robert Abel, a quiet, retired Nasa engineer. He confronted Abel outside his firm. They started arguing. Miller drew a .357 revolver. He held the gun to Abel's caput and demanded he confess to being a serial killer.

As Miller stared down the butt, he thought Abel's face was strangely impassive. Suddenly, he felt the anger flush from his body. He decided not to pull the trigger, for, he later claimed, two reasons: if Abel really were a serial killer, killing him would stop the possibility of identifying his other victims and bringing closure to their families. And if Abel really were some kind of psychopath, devoid of censor and incapable of remorse, then killing him would serve no real justice.

With that, Miller walked away. He broke down weeping, drove to a hospital and checked himself into the psychiatric ward. Past the time he emerged, 10 days subsequently, he knew he couldn't continue as he was. He had to aqueduct his grief more productively.

His mission, notwithstanding, wasn't over.

Sometimes, the women seemed to vanish into air. Their bodies were never establish, and their faces stood frozen in time in high school yearbooks, or memorialized by forensic sketches of what they might look similar, years later, if they were notwithstanding alive.

Other times, investigators discovered the remains of unknown victims, fated to be remembered by their constabulary aliases – "Jane Doe", "Janet Doe" – and doomed to take the morgue for final resting place.

The bodies were all found near Texas's I-45 expressway, which threads its way through Houston's urban sprawl into the coastal manifestly before ending at the island of Galveston. Over the years, the route has earned a grim nickname among cops, offense buffs, and armchair detectives: the "highway to hell".

Journalists and law enforcement officials believe at least 30 women and girls were abducted, raped and murdered between the 1970s and early on 2000s – the victims of a series of overlapping, perhaps unrelated, killers, who turned the area into a kind of Bermuda Triangle of violence and sexual predation.

For iii decades, killers stalked the area with credible impunity. In recent years, thanks in part to improvements in forensic technology, law enforcement agencies have arrested or named suspects in some of the killings.

Many cases, however, remain unsolved – including the case of Tim Miller's own daughter, Laura.

In 1984, Laura, 16, was abducted and murdered past an unknown attacker. Her expiry set Miller on a one-human being crusade – organizing search parties, goading the police investigation, and working to solve not simply Laura'south example but all cases of missing women in the surface area.

Miller developed considerable expertise at finding missing people, or their bodies. Families and law enforcement agencies beyond the country began contacting him for his help in cases of all kinds: missing dementia patients; lost toddlers; planes disappeared over body of water; and suspected homicides – a seeming avalanche of murder cases, hot and common cold alike.

In 2000, Miller founded Texas EquuSearch, a search-and-recovery non-profit which has assisted with hundreds of missing-persons cases and located more 400 living people and 238 bodies, according to the organization. Miller and his squad have searched for missing people, or their remains, in every kind of river, lake, retention pond, bay, bayou and canal, using everything from scuba divers to sonar to tiny robotic boats.

When he isn't looking underwater, Miller looks nether the globe. Once he dug the foundations out from nether a house, looking for bodies. He didn't find any, though he found a suspiciously body-shaped hollow in the world.

Fifty-fifty when he isn't leading a search, or managing his day chore – a construction business – Miller seems to find himself digging. "I was on my tractor from dawn to sunset yesterday, moving dirt," he told me when I met him. "Stress relief."

In person Miller, 71, calls to mind a coiled spring, rusted, but still strong. He radiates restless energy – pacing effectually in his brown cowboy ropers, fumbling cigarettes from a shirt pocket, balancing a phone in the cheat of his neck, fielding phone calls from victims' families, FBI agents, sheriff'south deputies.

The one example Miller has never been able to shut, still, is the 1 that started him on his strange mission in the showtime place: his daughter's murder.

Simply now, three decades after, he believes he knows who did it.

If Miller could go back, rewinding time like spools of tape, he would cease his girl on the moment on x September 1984, when Laura went to employ a payphone at a nearby gas station. The Millers had recently moved into a new house in League Metropolis and their phone lines weren't set up upwards yet. Laura wanted to call her boyfriend.

She was never seen alive again.

Laura suffered seizures, so when she failed to come home her parents' first impulse was to bank check area hospitals. That yielded nothing, and Tim and Janet Miller turned to the law. Laura also had a history of depression and feet; her great dear was singing, and her self-esteem never recovered after she was humiliated by a seizure assault during a solo at her school Christmas recital. Because of her mental health problems, police investigators insisted on treating her as a possible delinquent or suicide.

Initially, nobody noticed that Laura had disappeared 11 months to the twenty-four hours subsequently another woman – from the same gas station, while using the same payphone.

Heide Fye, a 23-year-sometime waitress, disappeared on 10 October 1983. On 4 April 1984, a couple in League City noticed their dog playing with something in the k. Information technology was a human skull. The canis familiaris had dragged the skull from an overgrown nearby oil field on Calder, a deserted I-45 feeder road, and brought it dwelling house to testify the couple's toddler.

The police soon found the rest of Fye'southward torso in the oil field. She appeared to have been beaten to death with a blunt instrument. The police force had no leads; the family unit were left to their grief and the rest of the world moved on.

When Miller raised the connection, the police and the local press were, according to Miller, dismissive. "They said Laura was a 'known runaway'," Miller says. Xxx-v years later on, anger nonetheless ripples under the surface of his face. "They said Heide Fye was a 'known drug addict'."

Miller urged the police to search for Laura in the oil field on Calder Road where Fye had been found. They ignored him, he says, and refused him permission to search the field himself. (The League City police department declined my interview requests.)

Two years later, boys riding dirt bikes virtually the oil field smelled a foul odor. They thought it was a expressionless animal. It was the decomposable torso, six to viii weeks dead, of an unidentified young woman, known to this day as Jane Doe. She had been shot. Her body was propped nether a tree, about 150 feet from where Heide Fye had been establish.

While searching the field, police besides came across the skeleton of Laura Miller.

Tim Miller had already had a tough life before his daughter disappeared. As a child he was abandoned by his parents and lived with a serial of abusive relatives. His adult life wasn't much better; his infant son died in the crib and, a year earlier Laura was murdered, his brother killed himself. Throughout he'd managed to endure – until Laura.

At present his life complanate. God hated him, he believed, and was punishing him for some reason Miller didn't empathise. He began drinking. He and Janet divorced. He sank into his anger and despair like a strangely comforting cocoon. He spent long hours replaying the circumstances of Laura's disappearance, thinking near what he might have done differently, fantasizing most revenge.

When her body was found, Laura appeared to have been dead longer than Jane Doe, the unidentified woman plant adjacent to her. Because of her more advanced country of decay, the medical examiner was unable to identify the specific cause of death.

Like the other 2 bodies found in the oil field, Laura'south was propped against a tree, facing the sky, in a manner suggesting their killer liked to return to admire his work. Miller began staking out the field. Night after night he lay in wait with a gun, drinking and smoking in the dark, watching for Laura'southward killer to show himself.

He had one idea who might have done it. A man who lived downwards the road from the Millers when they lived in Dickinson, Clyde Hedrick, had recently served a brusque stint in prison for a foreign incident that occurred the same yr Laura was killed.

Hedrick was a sociable guy. He was leanly handsome – earlier a much later bout of jaw cancer, his near striking feature was his jawline – and a good dancer. One July night in 1984, he was hanging out at a nightclub he frequented, the Texas Moon, drinking and dancing with acquaintances, when they introduced him to a 29-yr-onetime woman, Ellen Beason. At some point that dark Hedrick and Beason left the club together. The next day she failed to show upward to work.

When confronted by authorities, Hedrick said that Beason had drowned while skinny-dipping and he'd panicked and hidden the body. The corpse was in a ravine near the Galveston Causeway, under an old sofa. The Galveston county medical examiner ruled Beason's cause of death indeterminable, so Hedrick was convicted only of abusing a corpse, a minor criminal offense, and sentenced to a yr in jail.

From Laura's beau, Miller heard that Hedrick knew his daughter and sometimes talked to her when she passed his house. One time she and some friends even apparently visited his house to buy pot.

Miller took his research on Hedrick to law enforcement officers. They were unimpressed by the rather circumstantial case he sketched for them.

In 1991, v years subsequently Laura's trunk was discovered, horseback riders on a path through the Calder oil field came across some other female body. The fourth adult female discovered there, she appeared to have been killed with a blunt instrument. Like Jane Doe, this victim could not be identified, so police dubbed her Janet Doe. Unlike Jane Doe, Laura Miller and Heide Fye, Janet Doe was laid out in the open, face-downwards, leading investigators to speculate that she was killed by a different person.

Miller still idea Hedrick might be responsible for the first iii victims. Past this point the 25-acre plot had earned the proper name locals had taken to calling it: "the killing fields".

Miller accused the League City constabulary and Galveston county medical examiner of incompetence, noting that Laura and Jane and Janet Doe had all probably died subsequently authorities knew a killer was in the area. It was fourth dimension, Miller decided, to open his own investigation. He tracked down the owner of the oil field and persuaded him to let Miller lease it for $10 a year.

Miller was convinced that out there, somewhere in the clay, was the clue to his daughter's killer. He organized volunteers to canvass the land for bodies and evidence. He drained a pond. He combed the land with cadaver dogs; he attacked the land with a backhoe. Every fourth dimension a domestic dog signaled, or a volunteer noticed a piece of litter, or he had any kind of hunch, he dug another hole.

Soon the field was pitted with craters. It began to seem as if he was at state of war with the earth itself.

But past then at that place was a new evolution. Police finally had a doubtable, and it wasn't Clyde Hedrick.

Information technology was Robert Abel, the retired Nasa engineer, and he owned a ranch right next to the killing fields.

Robert Abel was a "strange character ", Miller says, though not one who would strike most people as menacing. "A slightly built 60-twelvemonth-old with thinning brown hair and a mustache, Abel walks stiffly because of a bad back, wears reading glasses, and takes pills for his high blood pressure," journalist Skip Hollandsworth wrote in 1999 in Texas Monthly. He seemed "almost shy", Hollandsworth added, someone who "tends to put his hands in his front end pockets when he speaks".

Abel was the scion of an old Texan ranching family, and a vivid engineer. He was recruited by Nasa presently after graduating from university, and helped design the Saturn rockets that got the Apollo astronauts to the moon.

In 1983 Abel moved to League City. He leased a m acres of pasture on Calder Road, adjacent to the oil field, and in 1990, shortly afterward retiring from Nasa, he bought another 11 acres next to the oil field. He transformed the property into "Stardust Trailrides", a recreation center where companies could hold western-themed employee days and people could take photos of their children riding ponies.

Investigators approached Abel later they discovered Janet Doe, the fourth trunk in half dozen years, in the oil field. They were surprised by Abel'southward enthusiastic, virtually overenthusiastic, interest. He asked lots of questions about the investigation; he offered to help any mode he could; he even loaned horses and a backhoe to aid the police force search of the nearby state.

Of course, wouldn't anyone be interested if four expressionless bodies were institute right side by side to his property? Wouldn't he enquire lots of questions? Wouldn't he offer to help any way he could? But something about Abel struck police as off.

Then League City detective Gary Bittner received an unexpected telephone call from Abel's third ex-wife, Paula Myers. Abel had a sinister side, she said, and explosive bouts of anger and cruelty. He had never hurt her, but she'd witnessed him beating his horses, a claim corroborated by Cindy Jacobs, another of Abel's ex-wives. Jacobs' marriage to Abel had ended after just 41 days, and their friends and acquaintances had always wondered what happened. Now investigators learned the reason. Jacobs had declined sex with Abel i evening and, she said, he flew into a frightening rage.

Myers told police some other foreign item: when livestock died on Abel'due south ranchland, he left their bodies out to be eaten by scavengers. Hearing that, ane couldn't assist but think of the four bodies posed and left to rot in the oil field. But who would dump multiple bodies next to his own property?

The League Metropolis police force and the Houston FBI asked the FBI's Behavioral Science Unit in Quantico, Virginia, for assistance in compiling a profile of the killer. Results came in: the killer would exist highly intelligent, big-headed virtually his intelligence, and given to outbursts of anger. He would take a history of bad relationships with women and cruelty to animals. He might alive well-nigh the crime scene. He would closely follow news coverage of the killings and, if presented with the opportunity, he might effort to infiltrate the investigation nether the guise of assisting.

Although the police had no evidence linking Robel Abel to the murders, in 1993 they used the FBI profile to convince a approximate to grant a search warrant. Investigators searched Abel'south house and property for 12 hours. They took a golden tooth they found, in case it was a gift Abel had taken from i of the victims; they took his guns, to check them confronting a bullet establish in Jane Doe; they took news clippings he'd collected nearly the killings; they took his collection of amateur photography, in case he'd photographed the victims; they fifty-fifty took the cords from his window blinds to see if they could have been used for strangulation.

The law tested everything and arrived right back where they started. The tooth was Abel's. The bullet from Jane Doe was too corroded to lucifer to Abel's guns. The photos yielded zip. There was still no concrete bear witness linking Abel to the killings.

But Tim Miller had been post-obit the investigation carefully, and at present he, too, believed Abel had killed his girl.

Miller decided that if the law couldn't show Abel had done it, he would. "I made Robert's life pretty miserable," Miller told me. "To say the least." He began parking his auto outside Abel's business firm, making no effort to conceal his surveillance; he wanted Abel to know he was watching. "I would go by his house so much it was nuts," Miller said. "Two, three times a 24-hour interval." He left threatening letters.

Abel got a restraining guild. Miller kept watching Abel'due south house anyway, parking his car a few anxiety past the property line. One day, according to the 1999 Texas Monthly commodity, Miller chosen Abel and told him he planned to kidnap him, drive him to Nevada, and bury him alive in the desert.

He didn't. But he did face up Abel outside his house, put a .357 to Abel's head, and demand he confess to killing Laura, earlier driving away and checking himself into the hospital. (Abel afterwards denied the gun incident occurred, possibly, co-ordinate to Miller, because Abel was embarrassed.)

In the years that followed, Miller threw his energy into helping missing-person searches across the state, and became a frequent guest on unsolved-crime shows like America's Near Wanted. One of the lessons he'd learned from Laura's disappearance was the importance of stoking attention on cases: go on the media interested, and the police force under force per unit area.

Then information technology happened again. In Apr 1997, 12-twelvemonth-erstwhile Laura Smither disappeared while jogging virtually her Friendswood domicile. Her body was constitute afterward that month in a retention swimming in Pasadena. Four months afterwards, 17-year-old Jessica Cain disappeared, and her empty automobile was establish on the side of I-45. People wondered if the killer was back or it was a new one.

After Cain disappeared, Miller and 2 hundred local people decided on a unilateral search of Abel'southward property, without a search warrant and without his permission. They marched on to the ranch and raked information technology over, looking for bodies. They institute none.

By this betoken, Abel was a lonely man. His once-prosperous trail-rides business was going under for lack of customers, a blow that struck particularly difficult. "Robert was a rocket scientist, literally, but a country boy at heart, and he loved Stardust Trailrides," Miller says.

A disturbing realization began to nag at Miller. What if Abel wasn't guilty?

And and so some other. What if it was Hedrick all forth?

Miller told me he deeply regrets his role in rallying people against a human he believes in hindsight was not guilty. The two men reconciled a few years before Abel died. They passed each other driving and Miller hailed him. They pulled their cars over and Miller approached him. "I said: 'I'g gonna enquire for forgiveness, and I know I practise non deserve it.'" He asked Abel if he could hug him. They both cried.

In 2005 Miller was working a search in Aruba when an FBI amanuensis called.

"Did you hear the news?" the agent said. "Robert Abel is expressionless."

A railroad train struck Abel as he drove an ATV over a runway crossing most his family unit ranch in Bellville. The train engineer later on told Miller that Abel was braked next to the rail crossing, watching the train, waiting.

In 2010, Miller approached Richard Rennison, an FBI agent, and Tommy Hansen, a lieutenant with the Galveston sheriff's office, to urge them to investigate Clyde Hedrick equally a suspect.

The timing was good; Hansen had recently retired but stayed with the Galveston sheriff in a special part-time position, working the office's cold cases. Miller persuaded them to look at the enquiry he'd compiled, and they agreed to form a taskforce. The offset particular on their agenda was taking some other look at the case of Ellen Beason, the woman who supposedly drowned in Hedrick'south visitor in 1984.

Hansen and Rennison learned something interesting. In 1993, the police force had quietly exhumed Beason'south trunk and sent it to be evaluated past Harrell Gill-King, a forensic anthropologist at the University of North Texas. During the original investigation, the Galveston medical examiner, William Korndorffer, had alleged Beason's crusade of expiry indeterminable; but Gill-Rex took one look at her remains and saw that her bones had never been properly cleaned.

Afterwards cleaning her skull he found a long fracture, the kind that could just have been inflicted by considerable forcefulness.

In the bound of 2012, Rennison and Hansen ordered Beason'southward remains over again exhumed, and again sent to Gill-King for dissection. A new cause of death was issued – homicide. On four Apr 2013, 28 years afterwards he was convicted of tampering with Beason's corpse, Clyde Hedrick was arrested for her murder.

Presently before trial, three inmates in jail with Hedrick contacted the prosecutor's part. They claimed that during a jailhouse chat Hedrick had not only admitted to chirapsia Beason to expiry with a table leg merely likewise to murdering Laura Miller and Heide Fye. He'd bragged about having sex with Laura before killing her.

During the trial the prosecutors filed a document, State's Notice of Intent to Use Evidence of Other Crimes, Wrongs, or Acts, containing a number of allegations apparently sourced from Hedrick's ex-wives, ex-girlfriends, jailmates and others. Although the allegations, most of which are unproven and speculative, have no legal bearing, they paint a nighttime pattern.

In improver to accusing Hedrick of physically assaulting former partners and molesting their children, the document alleges that in 1984 "the Defendant had sexual intercourse with the deceased body of Ellen Beason"; that betwixt 1991 and 1993 he "would come up dorsum habitation with a different shirt and would exist saying repeatedly that he had 'done it again'"; that "on or nigh 1996" he "came home with a bloody pocketknife", asked his then married woman to "get rid of it" and "dyed his hair and shaved his bristles"; and that in 2013 Hedrick "stated that he has murdered four to five women during the course of his life".

Miller sat in the court every mean solar day of the trial, staring at Hedrick. "We had a lot of staring contests," Miller told me, "and I won every fucking i of them." Miller never spoke, only the jury probably got the message. The facts of the case were likewise hazy to prove Hedrick intended to impale Beason, nevertheless, so he was convicted of involuntary manslaughter and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

The letter arrived in a plain envelope addressed in tight, careful cursive. A little salutation – "God Anoint Ever" – was scrawled over the back flap, perhaps as a greeting to the prison censor. The sender'due south return address was Terrell prison house in Rosharon, Texas.

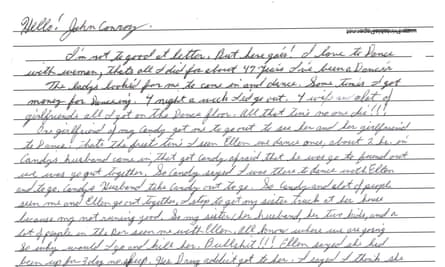

4 weeks earlier, I had contacted Clyde Hedrick to hear his side of the story. In his letter, he was steadfast that he never killed anyone, and he accused Miller of leading a campaign of persecution confronting him.

"2 trials two times for the same thing," he complained:

"One not Guilty, one Guilty, because of Miller and his friend[south]!! I get xx years, I'k on my 6th twelvemonth now. My wife and girl and friends still come to see me for a little moral support and pray that I'll come home soon. They [know] I didn't do it I had no contact with Miller girl at all someday, so assistance me God, I didn't do annihilation to anyone."

Hedrick argues he couldn't have acquired Ellen Beason'southward expiry. For one, he wrote, information technology wouldn't have fabricated sense for him to kill Beason, given that numerous witnesses had seen them together that night. ("All know where we are going so why would I go and kill her. Bullshit!!!")

He also reiterated his claim that his decision to hide Beason'southward body was motivated by fear of being wrongly accused of her decease. In response to a primal bespeak raised during trial – that drowned bodies sink, rather than float, every bit Hedrick described Beason's trunk doing to investigators – he suggested that Beason really died in the h2o of a drug overdose.

"Miller got alot of people to recall I'm the League City Killing Field Serial Killer," he added, describing Miller as a vindictive human being with a compulsive need to point blame. "I'm the fourth human being he sayed got to be the one. All of u.s. acquired his girl death. Come on. [I desire] this nightmare over and behind me!"

In a phone conversation, Hedrick's mutual-constabulary married woman, Gladys McKnight, told me Miller had ruined her life. "That was one of my biggest fears all my life, growing old solitary, and that'south what looks similar is happening. I was used to Clyde taking care of me. I still miss him, and withal dear him. I've been in calumniating relationships, and Clyde was kind to me. He never raised a manus to me."

"Nearly 71-year-olds are sitting on La-Z-Boys, watching Oprah with their friends in the nursing home," Miller said, grinning, or peradventure grimacing, at the image. "I ain't e'er had bedsores." He leaned against his pickup.

It was a hot afternoon on his small, seven-acre ranch in Santa Atomic number 26, Texas. His horses grazed in a pasture. Behind the states was the barn where he houses EquuSearch'due south armada of boats and trucks. Inside, the barn was cool and smelled similar soil. Hanging from the wall were several huge sieves; on searches he uses them to sift os fragments from dirt, like panning for gold.

Miller prefers his easily, and mind, occupied with a task. On the rare moments he'south nonetheless, he has time to think – and when he thinks, he says, he gets into "trouble". So he works. When he isn't working a search operation, or his daughter'south case, or managing his construction business, Miller is out on the ranch, tending to the horses or repairing outbuildings.

If Clyde Hedrick really did kill Laura Miller, he might discover forgiveness from an unlikely quarter. It took him at least 25 years, Miller reckons, to come to a point where he could forgive his daughter'southward killer, simply he has.

Rape-murder is a capital offense in Texas, meaning Hedrick could face the death sentence if convicted of killing Laura. Were it up to Miller, withal, he'd grant full immunity to Clyde – every bit he always calls him, although they've never met – in commutation for a confession and the identities of other victims. He wants to requite closure to their families, even though, he knows from feel, true closure is a myth.

Are monsters born, or made? That question – nature versus nurture – is the most cardinal in criminology, and information technology cuts to the heart of questions almost human nature and the assumptions underlying our justice arrangement. Forensic psychologists believe serial rapists and killers develop an obsessive need for command as a response to humiliation and shame in babyhood. In a sense, they are products equally well equally transmitters of trauma.

Clyde Hedrick had a traumatic childhood, according to Miller, who, at this point, probably knows more about Hedrick than almost anyone. Hedrick'due south father went to prison and his adoptive stepfather allegedly driveling Clyde and his siblings "physically, emotionally, and sexually".

Yet Miller did not become an declared killer, and his own childhood was arguably only as bad. His male parent, a gambling addict, walked out on the family when he was a child. One mean solar day when he was six months old, his mother put Tim in a dresser drawer and set the house on fire with him and his brother within. 1 expert thing did happen to him, though. After a string of horrible experiences, the teenaged Tim was taken in for five years by a farm family in Ohio.

"They gave me that little chip of structure, lilliputian bit of unconditional love that I needed," he said. "If they hadn't taken me in, I truly believe I would be expressionless or in prison house today."

Miller claims he'due south bought a Bible for Hedrick and underlined passages in it about forgiveness. He told me he plans to give it to him if he ever has the opportunity.

I wondered if he'd underlined the Parable of the Lost Sheep: Which of you men, if you had one hundred sheep, and lost ane of them, wouldn't go out the 99 in the wilderness, and go afterwards the 1 that was lost, until he found it?

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/jun/12/tim-miller-can-find-almost-anyone-can-he-find-his-daughters-killer

0 Response to "tim miller husband"

Post a Comment